Scientists Say Ice Lurks in Asteroid's Cold Heart

"For a long time the thinking was that you couldn't find a cup's worth of water in the entire asteroid belt," said Don Yeomans, manager of NASA's Near-Earth Object Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Today we know you not only could quench your thirst, but you just might be able to fill up every pool on Earth – and then some."

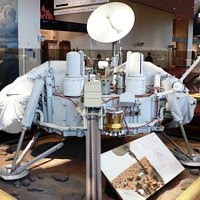

The discovery is a result of six years of observing asteroid 24 Themis by astronomer Andrew Rivkin of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. Rivkin, along with Joshua Emery, of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, employed the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility to take measurements of the asteroid on seven separate occasions beginning in 2002. Buried in their compiled data was the consistent infrared signature of water ice and carbon-based organic materials.

The study's findings are particularly surprising because it was believed that Themis, orbiting the sun at "only" 479 million kilometers (297 million miles), was too close to the solar system's fiery heat source to carry water ice left over from the solar system's origin 4.6 billion years ago.

Now, the astronomical community knows better. The research could help re-write the book on the solar system's formation and the nature of asteroids.

"This is exciting because it provides us a better understanding about our past – and our possible future," said Yeomans. "This research indicates that not only could asteroids be possible sources of raw materials, but they could be the fueling stations and watering holes for future interplanetary exploration."

Rivkin and Emory's findings were independently confirmed by a team led by Humberto Campins at the University of Central Florida in Orlando.

NASA detects, tracks and characterizes asteroids and comets passing close to Earth using both ground- and space-based telescopes. The Near-Earth Object Observations Program, commonly called "Spaceguard," discovers these objects, characterizes a subset of them, and plots their orbits to determine if any could be potentially hazardous to our planet.

JPL manages the Near-Earth Object Program Office for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.